Free Palestine AND Free Ukraine?

Reconsidering our approaches to solidarity, imperialism and global justice

Hello, bonjour, marhaba, kia ora, boozhoo! If you’re new here, I encourage you to check out my “About” page to learn more about this blog.

From August of 2022 to March of 2023, I worked for a humanitarian aid organization in the city of Dnipro, Ukraine. Shortly after I arrived there, a friend of mine shared Yev’s Patreon page with me. Patreon is a website where creators of all types can earn some income through paid subscriptions from followers. Yev has since closed his Patreon, but at the time he was using it to share his perspective as a queer leftist Ukrainian.

I remember one of his weekly audio updates in particular. He described waking up to a loud explosion with grumbling thoughts of “not again”. After a moment of risk-weighing, the sleepy side of the brain won with “it was probably just that one” and he closed his eyes. Just half a minute later though, there was another explosion and he thought “ok, I should probably move away from the windows and find shelter somewhere more central in the building.”

Despite Dnipro being a city of one million people, I felt very isolated there, mostly only socializing with my coworkers. It surprised me to hear this retelling of something I’d experienced coming from someone I didn’t know. And moreso, Yev was speaking in English, a language I rarely heard in public. I didn’t know that I needed to hear it, but his description of that attack acted as an affirmation of the trauma slowly building in my system.

Feeling like I was sending fan mail, I reached out to Yev on Patreon and asked if he’d like to meet in person. He introduced me to a coffee shop which I then became a regular at. As I came to find with many coffee shops in Ukraine, its interior could’ve been featured in a magazine. It had high ceilings, exposed brick, and huge windows with natural light. The hipness of its contemporary light fixtures and large indoor plants were only one-upped by the macrame hammock seat.

When I commented on the great vibe, Yev began to joke about how many foreigners have a misconception of Ukraine as being a poor country, stuck in the soviet era, when it is actually full of leading scientists and creatives in all art forms. Throughout our following conversations, Yev enlightened me on the immense cultural diversity of Ukraine and how it has been damaged by Russia’s influence before, during and after the USSR.

Historically, Dnipro has been a Russian-speaking city (look up “Russification” if you’re curious why). As a result, Yev grew up speaking Russian and learned Ukrainian in school. At the same time, he learned English through the media. He told me “it was the only way to learn more about queerness at that time. The only queer people we saw were in English speaking shows, movies and on youtube.” So, while he grew up in Ukraine, in many ways he also grew up in the same online spaces as a typical Western gen Z kid. As a millennial who’s spent a lot of time online myself, I think I can say that both of us felt the pain of the internet outages caused by Russia targeting Ukraine’s power infrastructure. This disconnectedness affected our abilities to escape online and it certainly exacerbated my loneliness (not to mention my Duolingo streak). In January, when Yev managed to get a fiber optic internet connection (stable during outages), he told me, “I had it only for one day now but my mental health is already better.”

Still, where Yev might have found support among westerners online who claim to be anti-imperialist and pro-liberation, he instead felt abandonment. Especially from so-called “leftists” in the US. As a self-proclaimed leftist, I fought the urge to be on the defensive, and instead pushed myself to listen and understand. As a result, I was forced to think deeply about how my values are applied in the real world and diverge from what Yev calls a “fetishization” of the USSR-style communism that is common among leftists. While I’ve never called myself a full-fledged communist, my views on “communism” have certainly evolved since working in Ukraine and I’m now more of an “anti-communist communist” a la Margaret Killjoy’s blog.

After the attacks of October 7th and the horrific retaliation by Israel, I perceived some tension between Yev and I. Or maybe I just imagined it, as someone with a torn conscience might. As an American, I saw my country providing aid to Ukraine and turning around and committing genocide on Palestinians. Subsequently, I mostly only shared content online about Palestine, not Ukraine. When I saw Ukrainian friends view my Instagram stories, I imagined them judging me for my silence on Ukraine. I saw other friends and pages make comparisons between how Ukraine and Palestine are reported on in the news (see this Mondoweiss article). Whether or not it actually was, it began to feel like a competition. Complicating my feelings even more, I had the impression that Ukraine tended towards supporting Israel, or at least, “historic ties seem stronger than current disagreements”, as this article puts it. It makes sense that knowledge of ties between Hamas and Iran raised alarm bells among Ukrainians since it’s well-known that Iran supplies Russia with drones used in attacks on Ukrainian civilians. It wasn’t that I felt any less sympathy for either people group, but that it felt impossible to please any of my friends. I’m sure my brain is confusing solidarity with people-pleasing, but it’s hard for it to not be so personal when you have those kinds of relationships.

Feeling all this discomfort, I asked Yev what he thought about international solidarity, especially in the Ukraine and Palestine context. This is definitely a tough subject that I’m still unclear about myself. Considering Yev's calls for solidarity from the West, do you think solidarity should also be expected from oppressed nations themselves?

Yev’s insights bridge the gap between theory and reality, offering a much-needed perspective to the narratives that dominate leftist discourse. I hope that his experiences challenge you to rethink your approaches to solidarity, imperialism, and global justice, as they have for me. Finally, Yev’s call to action is this: to listen more carefully, engage more critically, and act more inclusively.

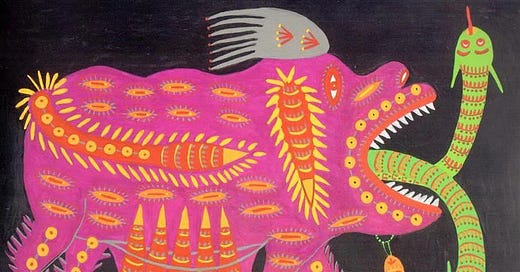

“Atomic War, Be it Damned” by Maria Prymachenko, 1978

Katy: Hi Yev, can you start us off by introducing yourself and giving us an idea of your personal political leanings?

Yev: Yeah, basically, I'm Yev. Politically, to go back to when I was a teenager, before the first invasion of Ukraine in 2014, I would’ve considered myself an anarchist. Not like a punk one, more like an annoying one - in an “intellectual” kind of way.

I remember, in my last years of high school we actually had defense classes in Ukraine. I was so annoyed, I was like, “why would we ever need this in real life? No one would ever have a war with us. We’ve never done anything to anyone.” We had this belief that it's all in the past. Like, Russia is a problematic country, but war was like… I couldn't imagine it, right? Obviously I wasn’t paying enough attention because Russia already invaded Georgia in 2008. So the signs were there, but we believed it somehow changed, it’s not what it used to be.

And then I learned the lesson because, literally a year after I graduated, the Russians invaded Ukraine in 2014. So that was kind of the first point where I think my views have changed. I realized why people need an army, why people need to have a defense, why people need protection and a lot of other things. And I understood that anarchism as an idea would be great. But there is also reality.

And then the second point obviously was the full scale invasion. At that point, I still considered myself very left-wing. Because I spoke English, I was immersed into the English-speaking left-wing - like the Western kind of world. I watched all the YouTubers, read the same people on Twitter and et cetera, et cetera.

One of the first things I realized was that I couldn’t speak up. I saw so many leftists repeating Russian propaganda, and when I tried talking to anyone who would listen, I was accused of being a Nazi. That’s why I started being active on Twitter—sharing my personal and family stories, but also talking about Russian colonialism in general, like many Ukrainians who speak English.

I think many Western people don’t know that many English-speaking, non-first world people, still try to participate in the discourse.

Our experiences and history are inconvenient for leftists in the West, as we refuse to glorify the Soviet Union. Our family history reminds us that the USSR was merely a rebranding of the Russian Empire—an extremely successful one.

I also taught Russian to foreigners and most of my students were Westerners from the U.S. I noticed they had absorbed so much Russian propaganda. It was shocking to meet Westerners who believed that so-called “Eastern Ukrainians” (Ukrainians like me who were Russified for centuries, therefore speakers of Russian language but still ethnically Ukrainians) were fighting for communism against Ukraine and that the Ukrainian state was somehow Nazi.

When the invasion happened, Russians were often invited to leftist panels to talk about Western imperialism, but Russian imperialism was rarely mentioned. Ukrainians were left out of discussions about Ukraine, like at Code Pink events.

I guess my political views are very complicated at the moment. I basically realized that no one would listen to us, to people from Eastern Europe, from Central Asia. And in those Western left-wing places, where they say that you should listen to the victims, and you should listen to the indigenous people or to the people from the region, - no one would ever listen to us.

Katy: Do you still consider yourself left-leaning at all or...?

Yev: Definitely, I lean left politically. I take a lot of pride in being from a region of Ukraine that had one of the most famous anarchist mass movement that ever existed. This was a grassroots, bottom-up movement of horizontal assemblies that was started by actual peasants opposing Russian imperial policies. This form of self-governance differed from the Bolshevik movement which was centralized in Moscow and imposed here.

I’m not communist though. For Westerners, this word, communism, is very fetishized. There's something exotic about it and for them it has one meaning, but for us it’s very different. For Eastern Europeans and Central Asians, it is authoritarianism. It's the opposite of democracy, of self-determination, of national identity, of having any say over your land and resources. You cannot say “that was just Russian communism, and this time we can fix it”. You cannot go with the same ideology that killed at least 6 million Ukrainians by starvation and millions more by just occupying.

But I definitely have left-wing views, not right-wing for sure.

Katy: Yeah, but I know it's hard to keep that identity when you're seeing a lot of bullshit coming from it. Do you feel like you’re ever at odds with other Ukrainians for your views?

Yev: Well, it depends. What Americans think of as left-wing is not considered very left-wing here. On political issues the majority of Ukrainians have left views like supporting universal healthcare, child support, market control, etc.

I guess on social issues many Ukrainians are more conservative. We’ve seen very big progress since we got our independence though. For example, the Soviet Union had laws that forbid women from doing around 600 certain jobs. We got rid of that and other such examples of laws. Ukraine was one of the first former USSR countries to decriminalize homosexuality. We've seen a lot of obstacles and reactionary movements, the same as everywhere else, but compared to Russia, that kind of progress is huge.

As far as governance, the choice right now is this authoritarian dictatorship conservative insane racist… or a very imperfect very young European style democracy. There aren’t many alternatives at the moment, so our brain doesn’t even go there. It's more like, the system is very imperfect and it should be changed, but we still need to preserve the democracy we have now.

Also, it's very common for Ukrainians to criticize the government. So it's very easy to find common language with the majority of Ukrainians. As a result, the society is not as polarized as American society and I don’t feel like I’m put at odds with others that much.

Katy: I want to ask you about some of the things that I often hear about Ukraine, here in the US. What do you make of the people that say the invasion was provoked by NATO expansion and that NATO should have been disbanded in the 90s when they had the chance, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union?

Yev: How come they had a chance in 90’s? Russia bombed Chechnya to the ground from 1994 to 1996 and occupied parts of Moldova. With such crimes being committed by Russia, why would anyone think NATO had a chance to be disbanded?

What do I think about NATO expansion provoking the war? Imagine if somebody tells you they will steal your land. You join an alliance to protect yourself and they say it provoked them to invade another country that did not join the alliance. That’s Russian justification that people in the West repeat because they believe Eastern Europeans can’t have a say in their own security.

it's like an abuser who says “well you provoked me to abuse you because you sought help from abuse, I had no choice but to abuse you again”. Eastern Europeans spent decades, and in some cases centuries, under Russian colonial rule so when they had a moment to seek protection in the 90s they did.

Just because Russia lost control over some of its colonies in the 90s, when the USSR collapsed, that doesn't mean Russia somehow changed. It became a smaller empire, but not less of an empire.

It's also a part of the crime, and Russian tactic in any war, to say "I am the victim, so I have the right to abuse you." It’s a very efficient tactic that can lead to becoming the biggest country on the planet by saying “you savages, I am afraid of you, so I will conquer everything from east of Germany and west of Japan to ‘feel safe’.”

Katy: Yeah, what you’re saying makes sense. NATO is definitely one of the areas I need to understand better!

Another message that I hear a lot is that we need to support our own people before we fund wars abroad. In principle, I agree with that, but I also understand, history makes it a lot more complicated. So I was wondering if you could explain how that is in the context of Ukraine, and how you would respond to that?

Yev: Well, I mean, the first thing is that, isn't it ridiculous that left-wing messaging is the same as right-wing messaging right now? It is in America at least, but also everywhere in Europe, too.

So, the question here is about funding the war, but in this case it’s also about funding the defense of the nation that was invaded. It's not the same as funding the war, because helping people to defend themselves might actually stop the war if they are funded efficiently.

There’s a really misleading narrative about aid to Ukraine. They talk about billions of dollars in aid, but in reality, that figure reflects the price of very old equipment donated to Ukraine. Much of this equipment is 50 years old or more and would have either been scrapped or would have cost the U.S. money to maintain anyway. By donating it to Ukraine, you would save money on maintaining it. But, they do this misleading thing where they name those prices in billions, but in reality, it is actually equipment that already exists and is being unused.

There is also money that never goes directly to Ukraine. A lot of that money stays in the United States, funding different types of jobs for aid to happen. For example, with the production of shells, you need a factory, you need to hire people. And this war is the most intensive war since, like, the World War II by the amount of shells used.

Lots of that money even goes to Moldova or to neighboring countries for humanitarian reasons and et cetera. But they just call it Ukraine aid overall.

Another thing is that you can do both, take care of your own people and help those in need abroad, even Ukraine did it during the war. The government still funds healthcare, education as much as possible and sends humanitarian aid abroad to places like Africa and the Middle East.

I’d also say it’s true that you should spend more money in the US, but that's a different dimension. That's a political dimension - are American politicians ready to spend money on social issues? That's more complicated.

Katy: In what ways do you think there is a lack of information in the US about Russia and the region?

Yev: Russia is the largest country in the world. It's actually a country that hides inside itself around 200 nations of different indigenous people. But that is really unknown for many people - even for many left-wing people who call themselves anti-colonialist, anti-imperialist.

Russia in the current form, right now, is the same country, the same system, that it was in the 19th century. Moscow steals their resources like gas from Bashkortostan and calls it “Russian gas”. Russia was doing to Ukraine centuries ago and is doing it now in Russian-occupied Ukraine, stealing grain and resources and shipping it around the world just like the 19th century.

Recently, there is more talk about the French colonization of America, British colonization, even Spanish colonization of America, but no one ever talks about Russian colonization of the region and also America. There are monuments to Russian colonialists standing in Alaska right now that indigenous people want to remove or have already removed. But that is never a topic in mainstream left-wing anti-imperial, anti-colonial conversations, even in America.

As a Ukrainian, I feel responsible to highlight Central Asia. We’re in the spotlight for a terrible reason—dying daily—but they could face the same tomorrow. Many now know about the Holodomor, but Russia caused a similar genocide by starvation in Qazaqstan against the Qazaq people.

No guarantee Russia stops if Ukraine gives in. Georgia lost 20% to Russia in 2008; it’s still occupied, with borders creeping yearly. Qazaqstan could be next.

If we look at Western academia, it barely covers Central Asia. Russia benefits from this ignorance—it could invade Qazaqstan tomorrow, call it Russia, and many wouldn’t notice.

So I feel the need to talk about not only Eastern Europe but Central Asia too. That was a big focus for us when we were writing “Matryoshka of Lies”. We didn't just mention it, but we also invited speakers from the region to talk about their experiences and expertise.

There is also the idea that old Western empires believe that Russia is a “superpower”. Ukrainian writer Oksana Zabuzhko calls this “Imperialist Solidarity”. You can just listen to what Russia has to say because as a “superpower” it has its “area of influence”. It’s what some call “Russia’s backyard.”

“The Threat of War”, Maria Prymachenko, 1986

Katy: Thanks for sharing those examples of regional solidarity. My next and last question is also on the theme of solidarity. I kind of hesitated to ask this one but I knew you would have a really good response and you said you were up for discussing it more.

So, I met some Ukrainians at the Democratic National Convention protest in support of Palestine. And I said, “Hi, it's really good to see you here. I also want to let you know, I understand that you guys feel abandoned by the left. And I just want you to know, I'm thinking about you guys.” And they thanked me, but they also said something that surprised me. And they said, “Well, solidarity goes both ways. How many other Ukrainians do you see here?” And I don't really know how to feel about that because like, it's true that we see there's a lot of solidarity with Palestine between the Black folks and Indigenous movements in the US. But also like, I don't want to place any expectations for certain behaviors on people that are under attack, you know. So, how do you feel about Ukrainian-Palestinian solidarity?

There’s so much here to unpack to address what might seem like a simple question.

First, we should be clear that Ukraine as a state has officially recognized Palestine and condemned the Israeli occupation. There is a Palestinian embassy in Kyiv, next door to the Portuguese embassy and Moroccan embassy, that were damaged in a recent Russian strike. And like, the Ukrainian government and its voting in the UN was so controversial that the Israeli ambassador called Ukraine an anti-Israel country because Ukraine voted against Israel in the UN quite a few times.

Ukraine has also donated a few tons of grain to Gaza. I understand that might sound kind of awkward, donating grain, but for Ukrainians, it's very symbolic. For Ukraine, it's food, it's bread. For people who survived genocide by starvation, bread represents a lot of things.

Secondly, and more in line with this question, I think Ukrainian leftists are increasingly understanding how solidarity with Palestinians is important for Western leftists. Even though we’ve often shared the same online spaces, our physical realities have been very different. Over the past few years, solidarity with Palestine grew in the West, while people in the East were preoccupied with the Russian threat. While the West focused on the occupation of Palestine, we were consumed with the occupations of Georgia and Crimea.

After 2022, when we posted in English about missiles hitting our hometowns, some of the first replies were things like, “Now post about Palestine like you post about Ukraine.” It was confusing, sad, and infuriating. These replies didn’t come from Palestinians but from people like a “Joe”, sitting in his house on stolen land in the States. This lack of self-awareness is maddening. This turned many Ukrainians against not just Western leftists but the Palestinian cause. Self-righteous, smug replies did more harm than propaganda ever could.

Over time, as Ukrainians adapted to full-scale war—living under missile attacks, blackouts, and water shortages—many of us began learning about Palestine and Israel. You could say that when October 7 happened, for many of us, Gaza appeared on the map the same way Ukraine did for many westerners in February 2022.

Understanding and forming our own views takes time—time Western Left’s self-righteousness doesn’t seem to allow us. We’re expected to immediately take sides, to perform “perfect victimhood,” or risk losing solidarity and aid while facing the threat of ethnic cleansing under Russian occupation. Some Ukrainian leftists now post performative solidarity online—adding “correct” flags, removing “incorrect” ones—just to be heard. “If that’s what it takes,” they say, “then why not?”

But real solidarity can’t be forced. It grows from genuine engagement and the discovery of what truly resonates with people. For Ukrainians like me, living through this war, solidarity is immediate. It’s with the barista acquaintance making coffee who was cleaning shattered glass just a week ago after a missile strike. It’s with a friend working as a nurse whose hospital was damaged in the same attack. It’s with the neighbor who lost a loved one, or the ex-classmate whose family lives under occupation. Our solidarity is with those we might not see tomorrow because our lives aren’t movies—and many won’t have a happy ending.

It’s easy to blame Ukrainians for not showing up at the DNC rallies in solidarity with Palestine. But maybe they’d show more solidarity if they weren’t so deep in this nightmare.

Katy: It must feel like a lot to have that criticism leveraged at you in the midst of an ongoing invasion. I guess you’d say that just adds to the abandonment that you already felt from the Western left?

I feel abandoned by some people I thought had ideas that should help us. But I don't feel like I need solidarity from all people groups. Take Black Americans for example. Even though we share a lot of similar history, if they think there’s something that matters more to them, I think that’s fine. I also understand that American politics and views on colonialism are very racialized. As white people, we are usually seen as those who perpetrated colonialism, not as people who suffered or continue to suffer from it. This perception is understandable, given how colonialism looked in the Americas. (Sidenote: look up Taras Shevchenko and Ira Aldridge for a beautiful example of historic solidarity between Ukrainians and Black Americans).

On the other hand, there are people who have also historically suffered—and still suffer—from Russia. Naturally, I feel understood when I’m around them. Eastern Europeans, Central Asians—they obviously pay more attention to Ukraine too because, geographically and historically, they relate to us more. And I think that’s fine when people do that. It feels like deep, real solidarity—not just virtue signaling, you know?

I just really despise when people start comparing the oppressed, like, doing this genocidal Olympics - who suffered more, who did what, and etc. It feels like it’s becoming fandom-y, where people are like, “I like Katy Perry, no, Lady Gaga is better”, but it's applied to war and genocide. There are people who act like that, and that is a terrible thing to do, for both sides, for everyone.

We are in this kind of super awkward position, because Palestinians and Ukrainians are both in the spotlight. And when two are in the spotlight, people are like, “okay, what's the comparison?”

And obviously, that’s why authoritarians around the world keep winning. While leftists fight over which cause is more important, authoritarians unite and cooperate, and corrupt politicians play virtue signaling on Twitter.

More about Yev:

As a content creator, Yev has produced his own content on youtube and in collaboration with others. He has also worked as a researcher and writer for the podcast Matryoshka of Lies.

Additional Resources:

Ukrainer.net/en - for learning about Ukraine’s geographical and cultural diversity

Ukrainian Spaces - podcast amplifying diverse Ukrainian voices and decolonizing Ukraine conversations.

20 Days in Mariupol - A team of Ukrainian journalists trapped in the besieged city of Mariupol struggle to continue their work documenting atrocities of the Russian invasion - available on Netflix in some countries, Youtube or PBS

Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Freedom - A powerful documentary chronicling the 2013–2014 Euromaidan protests in Ukraine, where citizens united in a fight for democracy and human rights against government oppression - available on Netflix

Please note that I will be deleting comments that are flagrantly pro-Russian. I will allow those that ask genuine questions and open discussion.

Hey, I needed something like this. I'm from Moldova (mentioned a couple times) and while a leftist who likes the idea of communism I cant shrug off the immense weight it has placed on my country and my family too. My mom is almost blinded by capitalism, praises it just because she's known totalitarian communism and cant accept that there can be something better. I don't feel like I fit in with the usual Western leftists that are american exceptionalists and claim that there can only be one big great evil and that is the US. When the war started I was living in the West and got "cancelled" on twitter for saying that the Euromaidan was student-led and not an american psyop meant to destabilize Ukraine and create war... it's like we in Eastern Europe aren't allowed to have agency! I can recognize the imperialist expansion of NATO and the EU but I'm in constant fear of the war expanding, can't I want security? It's easy to speak from countries that were never ravaged by war, when my parents lived through the '91-'92 civil war created by Russia which ended with a thousand troops STILL stationed on our territory! I'm rambling with no end in sight but I just need leftist views from Eastern Europe. Why must we surrender to Russia?

Good piece. I think one thing that comes out of this is how limited the US world view is (still stuck in simplistic Cold War thinking, for example, and with a weak understanding on colonisation) and how self-referential, which is particularly problematic as the wealth and size of the US means it is influential beyond any actual value it offers, both in mainstream and leftist political circles.